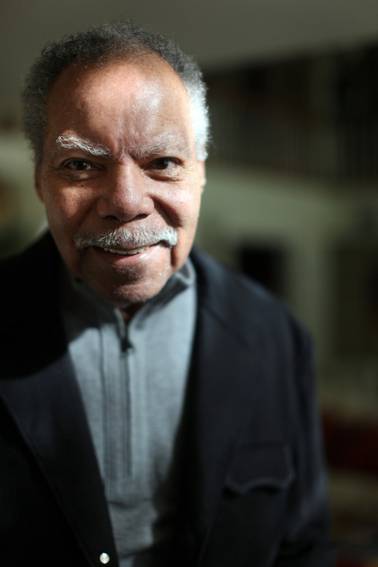

Bob Bailey will be remembered for civil rights leadership, having heart for all

During a long and colorful lifetime of firsts, Las Vegas’s Bob Bailey wore many hats.

Among them were crooner with the legendary Count Basie and his orchestra, road manager for his cousin singer Pearl Bailey, television variety show host, TV weatherman, Las Vegas’s first black disc jockey, nightclub owner, real estate developer, president of an economic development company and Nevada’s first black presidential appointee to a federal economic agency.

But no hat was more significant than the one he wore as a civil rights leader and the first chairman of the Nevada Equal Rights Commission during a period when Las Vegas’s practices were as Jim Crow as those in the Deep South. Working in harmony with fellow activists Charles Kellar, James McMillan and Dr. Charles West, Bailey was an effective instrument for change.

William H. “Bob” Bailey, who first came to prominence in Southern Nevada as the emcee for the Tropi-Can-Can Revue at the Moulin Rouge, Las Vegas’s first integrated casino in the 1950s, and went on to become a leading voice for economic development for minorities, died Saturday of natural causes. He was 87.

The family said Bailey died at Nathan Adelson Hospice from complications from Parkinson’s Disease.

Services for the Las Vegas resident of 59 years will be 2 p.m. Saturday at the Second Baptist Church, 500 W. Madison Ave.

“While my father taught me a lot about discrimination and that there are a lot of bad people in the world, he also said there were a lot of good people out there and that we should never forget those good people,” said Kimberly Bailey-Tureaud, a local minority business developer. “He had a deep love in his heart for everybody.”

Bailey kept that love in times when there was a lot of visible hate for people for people of color.

Once in the 1950s, Bailey tried to enter the front door of a Las Vegas hotel accompanied by his friend singer Nat King Cole and was stopped by a white security guard. Bailey said he and Cole had business in the hotel, to which the white guard responded, “I don’t care if you are here with Black Jesus Christ, you are not coming in here!”

A street and middle school in Las Vegas are named for Bailey.

The Las Vegas where Bailey arrived in 1955 was very different from what it is today, but not so different than in Dixie at that time, where Bailey graduated from a traditionally black college, Morehouse State in Atlanta, a classmate of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr.

Blacks in Southern Nevada at that time were forced to reside on the dilapidated “westside,” many in shack-like homes with no running water or electricity.

Black performers including Sammy Davis Jr., and Lena Horne thrilled crowds in Strip casino showrooms, but were not allowed to relax in the casinos or restaurants, swim in resort pools or be guests in hotel rooms. Instead, they had to stay in rustic West Las Vegas boarding houses.

Las Vegas hotels officially were desegregated in March 1960 during an accord reached by black community leaders including Bailey, local and state political leaders, police and three major Strip resorts, in a meeting at the Moulin Rouge that was moderated by late Sun Publisher Hank Greenspun. However, it took much of the 1960s to bring the uncooperative resorts on line.

To that end, Bailey, in 1962, was appointed by Gov. Grant Sawyer to serve as the first chairman of Nevada's Equal Rights Commission. Republican Bailey later said Democrat Sawyer had “a totally new vision” of racial equality for the state of Nevada.

But Baily’s task was by no means easy as at the time there were few restaurants or casino eateries in Carson City or Las Vegas where blacks were permitted to dine. Bailey and his staff conducted statewide hearings, subpoenaing resort owners, other business leaders and restaurateurs to answer why their properties continued to employ such discriminatory practices.

“I was warned that if I didn't stop subpoenaing, I may end up dead," Bailey recalled in a Feb. 26, 1996, Sun story. “They would drive by (my) house and throw a brick or something ... and I wouldn't know if it was a bomb or what it was.

“I really couldn't care less. I said, ‘If I've got to (die), I'll go this way.’”

Tureaud said her father would sit for many hours in a van outside of Las Vegas housing developments and document acts of discrimination — documentation that helped lead to passage of the state’s Civil Rights Act in the 1960s.

Bailey’s committee succeeded in opening employment opportunities for blacks and other minorities throughout the state.

“We have to remember that while every group has been subjected at one point in history to this kind of discrimination, it always takes more than that group of people to get out of that condition,” Bailey told the Sun. “There were some good people in this town who were very faithful to basically what was right.”

To Bailey, Sawyer was one of those “good people.” So much so, Bailey switched parties, became a Democrat and joined Sawyer on his campaign trail.

In his book “Hang Tough,” the late Grant Sawyer said that of all of the Las Vegas civil rights leaders of the 1960s. Bailey “may have been the most adept at balancing a passion for justice with an understanding of how to go about getting a system to reform itself.”

Bailey later authored his memoir, “Looking Up! Finding My Voice in Las Vegas.” Released in 2009, Bailey wrote about moving to Las Vegas and what it was like to be a black performer in what was then commonly referred to as “The Mississippi of the West.”

The road Bailey took to be a leader in the local phase of the Civil Rights Movement was strange in that unlike so many others he was not so political. In fact, Bailey often argued that he was not a politician, but rather a businessman. And, as it turns out, he was one heck of an entertainer too.

In the 1940s, Bailey sang with Count Basie and his orchestra, before taking the Moulin Rouge job, where he rubbed elbows with such frequent guests as Frank Sinatra and the other members of the Rat Pack, who would come to the West Las Vegas hot spot to unwind after their nightly Strip showroom performances.

Between his appearances at the Moulin Rouge, which operated for just six months before closing for what was termed as financial reasons, Bailey produced the “Talk of the Town,” a weekly TV variety show on KLAS-TV Channel 8.

The television show, which also ran for about six months, was hosted by Alice Key, a former dancer at New York's famed Cotton Club who went on to serve as Nevada's deputy labor commissioner.

The show featured a stream of all-star guests, including “Mr. Television” Milton Berle, Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington and Sammy Davis Jr. The program was said to have been the nation’s first show to be created by an entirely black cast and crew, but that claim never has been confirmed.

At the same time, Bailey hosted a radio show on KENO, thus giving him the honor of being Las Vegas’s first black disc jockey.

After the Moulin Rouge closed and Talk of the Town went off the air, Bailey left Las Vegas for two years to serve as the road manager for his cousin Pearl Bailey on her national concert tour.

When he got back to town, Bailey was the weatherman and movie host on Channel 8. Later, he moved to Channel 13 to host a show at the Fremont Hotel.

On his first day on that job Bailey was almost late because white hotel security guards refused to allow him to enter through the front door of the hotel-casino because Bailey was black, forcing Bailey to head to the alley and search for the back entrance into the place. That bigoted policy soon was changed and Bailey was allowed to use the front door for his subsequent TV shows.

Also at that time, Bailey hosted a live radio show from the lobby of the old Carver House hotel in West Las Vegas.

In 1965, Bailey opened the Sugar Hill nightclub at Lexington Street and Miller Avenue, a short distance from Bailey Drive, which was named after Bob many years ago.

Sugar Hill, which was in business for 26 years, early on was a Las Vegas celebrity hot spot noted for its Saturday night barbecue parties and jazz jam sessions, where stars including Johnny Carson would drop in to play drums and Louis Armstrong would blast out tunes on his trumpet.

In 1968, Bailey bought the Nucleus Plaza, then known as the Golden West Shopping Center, shortly after it was damaged by fire during riots that followed the assassination of Bailey’s friend and college classmate Martin Luther King Jr. Bailey spent $35,000 to refurbish the center

In the late 1970s, Bailey became the president of the Nevada Economic Development Co., which helped struggling minority-owned businesses with management and financing. He spent 19 years with NEDCO, raising $300 million to help launch local minority-owned businesses.

Bailey’s other assorted accomplishments in the Las Vegas business world included:

• Working with Operation Independence and the Stardust Hotel's casino management to create the first joint training program for black dealers.

• Starting an on-the-job training program for minorities at the Circus Circus hotel-casino.

• Developing a radio training school for black youth — the forerunner of KCEP radio.

• Working with the Clark County Economic Opportunity Board to create a card dealers' training school for minorities.

Bailey later estimated that more than 1,000 jobs opened up for minorities within two years because of those programs and others he helped institute through several agencies, including Manpower Services, which Bailey founded.

In 1990, President George Bush appointed Bailey to serve as deputy director of the U.S. Department of Commerce's Minority Business Development Agency. Bailey spent four years overseeing the operations and budgets of about 200 national agencies.

Bailey, who in the early 1990s was appointed president of the National Association of Minority Businesses, long said that his business philosophy was a simple one — education and training are the keys to success.

Born Feb. 14, 1927, in Detroit, the son of an auto worker, Bailey moved with his family to Cleveland after his father was laid off during the Great Depression. As a boy, Baily sang in church choirs and early on dreamed of joining his two cousins in the entertainment field.

In addition to Pearl, Bob’s other cousin Bill Bailey was a song and dance man who was the inspiration for the hit song “Bill Bailey Won’t You Please Come Home.” In fact, when William Bailey went into show business, he took the nickname “Bob” to avoid any confusion with his older more established cousin Bill.

While attending Morehouse on a musical scholarship, Bailey was singing in a nightclub when bandleader Benny Goodman approached him with an invitation to audition for Count Basie.

During his Christmas break from college, Bailey auditioned for Basie and got the job. After receiving his B.A. in business law at Morehouse, Bailey performed with Basie and his orchestra on “The Chitlin’ Circuit,” a string of black community theaters in major U.S. cities.

Bailey’s recordings with the Count Basie orchestra include “Blue and Sentimental” and “The Worst Blues I Ever Had.” He also recorded a version of the popular Irish ballad “Danny Boy.”

The Basie gig ended in 1950 and Bailey went to the School of Radio and Television in New York City to break into those mediums. But after he graduated, Bailey said he could not find work — especially on air — because of the color of his skin.

But Bailey got a big break when show producer Clarence Robinson, who had hired Bob for singing engagements in the past, was at the time putting together the soon-to-open Moulin Rouge show and asked Bailey to come to Las Vegas and emcee and sing in his new revue.

Strangely enough, that turned out to be Bailey’s ticket into television as the Moulin Rouge sponsored the Bailey-produced Talk of the Town on the Las Vegas CBS affiliate then owned by Sun Publisher Hank Greenspun, a crusader for equal rights who had no qualms about having a black man produce or host a show on his station.

Greenspun liked the show, which featured interviews with entertainers who were appearing in Las Vegas at the time. So much so, when the Moulin Rouge closed and producer Bailey lost his sponsor, Greenspun helped Bailey find new sponsors and kept the show going for a while.

Bailey eventually found himself on-air at KLAS doing a Sunday news commentary show.

In 1957, Bailey moved to Channel 13, where he not only hosted the variety show from the Fremont but also developed a teenage dance show.

In 1961, after returning to Las Vegas from the Pearl Bailey tour, Bob Bailey returned to Channel 8 to host a movie show and a talk show.

From 1965 to 1971, Bailey again worked at Channel 13 as a news broadcaster and as a variety show host.

Bailey also for several years wrote a column for the Las Vegas Sun.

Bailey eventually switched back to the Republican Party and was active in local GOP politics.

Bailey also was a real estate broker, having taken real estate classes at UNLV.

He received a Doctorate of Humane Letters from National University, San Diego in 1987.

On May 27, 1999, the Nevada legislature honored Bob Bailey and his wife of 63 years Anna L. Bailey, for outstanding and meritorious service to the state. Anna is a founding member of Las Vegas Links Inc. and Las Vegas Girl Friends Inc., nonprofit organizations that have doled out thousands of dollars in college scholarship money to young, promising Nevadans.

In 2005, the William H. "Bob" Bailey Middle School at 2500 N. Hollywood Blvd. opened in his honor. Bailey later called it the proudest moment of his life.

In May 2013, at the UNLV commencement ceremony, both Bob and Anna Bailey received UNLV’s highest honor — the Distinguished Nevadan Award.

Among his numerous other worthy deeds, Bailey helped develop the Latin Chamber of Commerce, the Minority Business Council and the Minority Contractors Association. He also served on the organizing board of the Black Chamber of Commerce and in the 1950s was the local chairman of the Urban Renewal Advisory Commission,

In addition to his wife, the former Anna Porter, and his daughter, Bailey is survived by his son, attorney son John Robert Bailey and five grandchildren, all of Las Vegas.

Ed Koch is a former longtime Sun reporter.